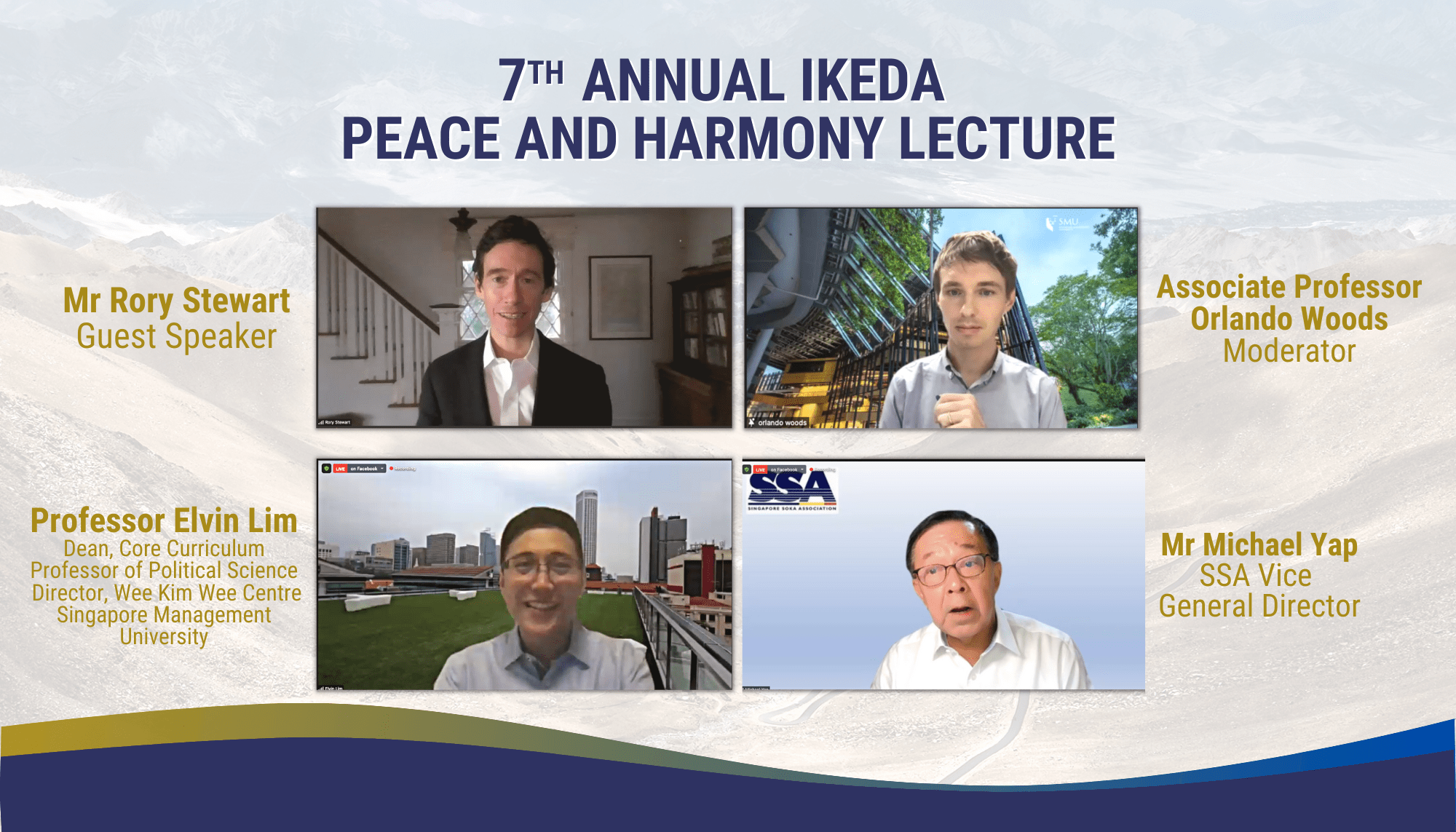

In collaboration with the Singapore Management University for the 7th year running, the Annual Ikeda Peace and Harmony Lecture conducted virtually this year on 23 September saw an overwhelming attendance of over 1,000 people in attendance. The lecture was also live streamed via the SMU Office of Core Curriculum’s Facebook page.

Invited speaker Mr Rory Stewart, Senior Fellow at the Jackson Institute, Yale University and Former UK Secretary of State for International Development, spoke extensively on the topic, “After Afghanistan – What’s Next?”. This topic drew much interest from the audience due to its relevance in the current times as it discussed the recent happening in Afghanistan.

Amongst the guests present for the lecture included Professor Wang Gungwu (East Asian Institute), Ambassador Ong Keng Yong (Executive Deputy Chairman at RSIS), Ambassador Mohammad Alami Musa (Head of Studies in Inter-Religious Relations in Plural Societies Programme at RSIS), Mr Asmin Buang (Executive Director of Perdaus), Mr Hussaini Abdullah (President of Pertapis), Mr Isa Hassan (Vice President of Jamiyah Singapore), Mr Ervad Rustom Ghadiali (Council Member of the Inter-religious Organisation of Singapore) and Sister Theresa Seow (Acting Executive Director from the Canossaville Children and Community Services).

Professor Elvin Lim, Dean of the Office of Core Curriculum (OCC) and Director of Wee Kim Wee Centre (WKWC) at the Singapore Management University, shared in his opening speech:

“I am happy to share that SMU enjoys this wonderful relationship with SSA since 2015, and this lecture series honors the wisdom and values of Dr Daisaku Ikeda.

Our theme this year for the students focuses on “War and Peace”, and we are particularly grateful to have Mr Rory Stewart to share his insights and experience with us.

The duality of war and peace is a curious thing. All too often, nations declare war in order to make peace. In the heat of the moment, this paradox is often lost on us.”

Michael Yap, SSA Vice General Director added,

“Throughout history, there have been times when encounters between different civilizations have led to unexpected results and triggered the tragedies of conflict and war. … Dialogue is what opens the eyes of the human spirit and liberates people from the curse of narrow-minded prejudices and hatred. Education must promote a truly cosmopolitan spirit that enables us to respect and learn from diverse cultures.”

This is the 7th in a series of lectures that SSA has collaborated with the Singapore Management University (SMU) that aims to fulfil SGI President Ikeda’s untiring commitment of dialogue for peace. For the past 6 years, the series has invited distinguished speakers to address and discuss ways in which threats and difficulties can be transformed into challenge, cooperation and growth.

Speech Excerpts by Mr Rory Stewart

The Age of intervention began in Bosnia in 1995 and accelerated with the missions in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq. Over this period, the United States and its allies developed a vision of themselves as turn-around CEO, who could parachute in, and almost regardless of local context, bring the strategy, and immense resources, that would enable them to fix things, collect their bonuses and get out as soon as possible. The symbol of the age was the American general, up at 4:00 a.m. to sprint eight miles before implementing his template to mend the failed state.

Had the same US and European officials been seeking to turn around lives in a poor ex-coal town in East Kentucky or to work with Native American tribes in South Dakota, they might have been more sceptical of blueprints for societal transformation, paid more attention to the history and the trauma of local communities, and been more modest about their position as outsiders. They might have understood that messiness was inevitable, failure always possible and patience essential. They might even have grasped why humility was better than a heavy footprint, listening than lecturing.

But somehow in Afghanistan and Iraq – places far more traumatised, impoverished and damaged than anything at home – US and European officials insisted that there could be a formula for success, a ‘clearly defined mission’, and an ‘exit strategy’. And explained any setback in terms of lack of international planning or resources.

Bosnia – the first intervention of the Age of Intervention – is an object lesson in the benefits of a light footprint. In Bosnia rights were upheld, abusers were held accountable, militias were disarmed, justice was done, and peace followed. Within a decade of the intervention, more than 400,000 soldiers in three armies had been disarmed and Bosnia had a unified army of 15,000. More than 200,000 homes were given back to their owners. All the major war criminals were caught and tried, and Bosnia’s homicide rate fell below that of Sweden. All this was achieved at a cost of zero American and NATO lives. But successes were due not to the strength of the international presence on Bosnia but to its comparative weakness. The foreign presence was vital for ending the war, protecting the peace, and for allowing an incremental principled path towards justice and refugee returns. But its limited powers forced it to act very slowly and make uncomfortable compromises (often to the fury of local activists), and to reinforce unexpected and improvised local initiatives, in which local politicians often took the lead.

The early light footprint in Afghanistan had potential as well. There was progress in the country’s central and northern regions as well, including in Herat, much of Mazar-e-Sharif, the Panjshir Valley, the Shomali Plain, and Kabul. In all these places, a light international footprint meant fewer international casualties, which in turn reduced the pressure on foreign politicians and generals to make exaggerated claims. It also forced the international community to engage in a more modest discussion with the Afghan people about what kind of society they themselves desired, and to accept ideas and values that Americans and Europeans did not always share. It forced a partnership.

Much of this progress was destroyed by the surge – which returned to the old model of plans and immense resources – undermining the Afghan state and provoking a Taliban insurgency. But a light footprint could have been sustained again after combat operation ceased in Afghanistan in 2014. The Taliban ultimately prevailed, not because they were on the verge of victory, but because the US chose to withdraw, crippling the Afghan airforce as they departed, and leaving Afghan troops isolated without air support and resupply, and feeling betrayed and abandoned. But the decision to abandon the light footprint in Afghanistan was not driven by military necessity the interests of Afghans, or the requirements of US foreign policy.

Instead, the light footprint, was a victim of the extreme optimism and pessimism, which characterises modern politics in the US and Europe. It represented the middle ground, in a politics that prefers to swing between extremes – from overreach and overstatement to isolation and withdrawal. This was particularly obvious in the attitude of former U.S. president Donald Trump. He swung from his predecessors’ argument that failure in Afghanistan ‘was not an option’, to the view that failure had no consequence: showing no concern for how a U.S. withdrawal would affect the United States’ reputation and alliances, regional stability, terrorism, or Afghan lives. And he responded to the previous exaggerated claims about Afghanistan’s importance, not with moderate claims, but with a refusal to maintain even the smallest presence there or to bear the slightest cost.

But the horrors of over-intervention and the problems of populism should not lead us to dismiss the potential of a more restrained approach to intervention. Interventions are unpredictable and chaotic, and can fail for reasons beyond anyone’s control. When they succeed, it is local political leaders, local institutions, and the regional context, not the quest for ever more perfect international plans, which are the key to success. But there will still be occasions when there are strong moral, and national security arguments, to intervene; intervention can work– as Sierra Leone and Bosnia and the no-fly zone in Northern Iraq demonstrate, and these successes have lessons for the US and its allies.

Foreign militaries should not lead counter-insurgency campaigns in another nation, but they can play a vital role in saving a besieged city (as in Sarajevo), or in reinforcing local initiatives (as with refugee returns). Foreign civilians should not pretend to reform rural governance in a conflict zone (where the key is local culture and structures of power), but they can transform specific technical sectors (from central bank reform to power plants and health procedures), and they can pursue patient and principled diplomacy (as they did with the International Criminal Tribunal, after the Bosnian intervention.). Interventions cannot remove the root causes of conflict but they can provide specific protection and relief, which make an immense difference to millions of lives.

Intervention is, therefore, an exercise in rational hope – a craft that demands deep experience, knowledge, prudence, small steps, limited concrete ambitions, and above all the patience and courage to let local actors take power and make mistakes. It should be modelled on the partnership, which you might form with a vulnerable community or individual at home. For these, and many other reasons, a restrained mandate, and a light footprint is preferable. Ever more developed plans, more resources, and more troops, tend to make things worse rather than better.

The fundamental challenge to a lighter and more restrained approach to intervention is not empirical it is political. And in particular the political pressures that make complexity, partial progress, and long-term patience – appear indefensible.

President Joe Biden was once an advocate for a light footprint—against the surge but also against total withdrawal —when he was Obama’s vice president. Over the previous decade, Biden somehow convinced himself that the light footprint had failed. But his light footprint did not fail. What failed was the political culture, and the imagination of our bureaucracies. What failed was the patience, realism, and moderation needed to sustain it.